What is an average season? Living in the good country, for now

Robyn Cowley, Rangeland Scientist, Darwin

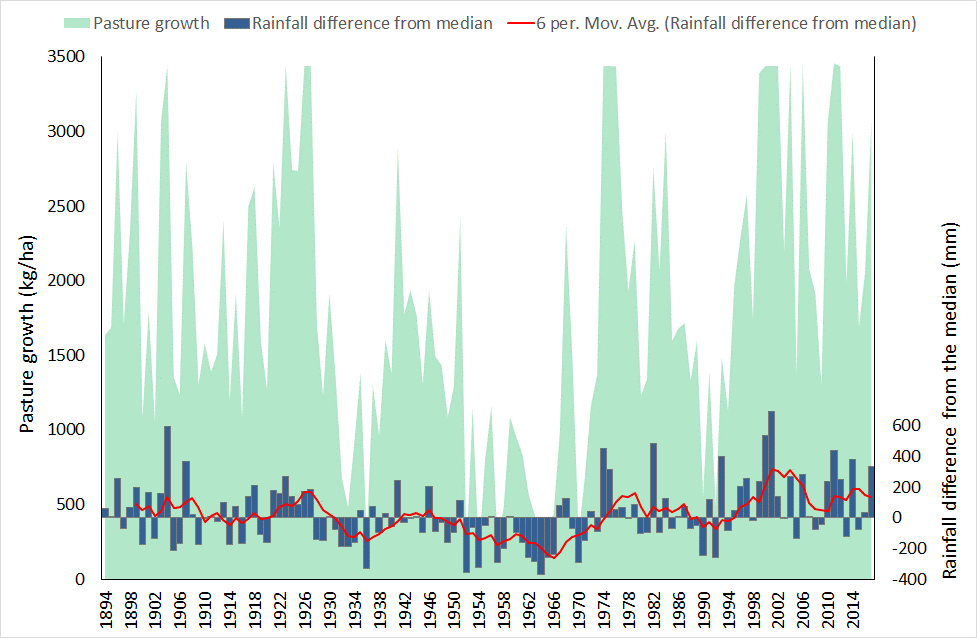

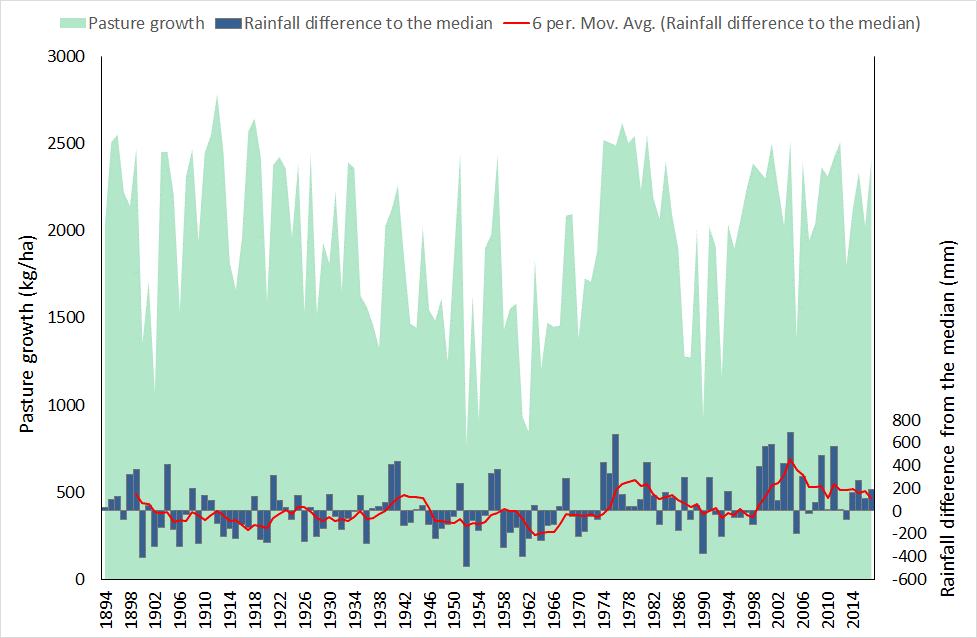

Rain in your part of the world has been pretty reliable of late. But if you’ve only lived here for the last 20 years, which seems like a pretty long time really, you might not realise how good it’s actually been. You just happened to have lived through the wettest period in the last century. Check out the rainfall and modelled pasture growth over the last century at locations in the central and southern Victoria River Downs (VRD) and Sturt Plateau in figures 10 and 11 and table four below.

Most of the last 20 years had above average growth, and any dryish year was backed up by an above average year. No drought, no worries. But if you were here between 1950 and 1970, it was a very dry affair, with mostly below average rainfall and pasture growth, although the pasture quality would have been a lot better, because in drier years the nutrients don’t get diluted in larger plants.

There tends to be cycles in wetter and drier periods. You can see the waves of moisture rolling in and out over the last century. But we’ve just had 20 wet years, so what’s next?

It depends who you ask. Some think that it might stay wetter, although it never has before, so this may be somewhat wishful thinking. Some scientists think that pollution in Asia has changed the monsoon to give us more rainfall. Well we better hope they don’t clean up their act I guess! The climate change projections for future rainfall are not too bad in this part of the world (similar or more rainfall), unlike in southern, eastern and south west Australia, where it is projected to get drier. But unfortunately just about every climate change model has a different opinion about what’s going to happen to rainfall, so your guess is probably as good as theirs.

So, assuming the rainfall is roughly going to be the same, but still variable – drier times are probably coming.

Figure 10: Modelled pasture growth and rainfall (difference each year from the long term median) over time on an alluvial land type in the southern VRD.

Figure 11: Modelled pasture growth and rainfall (difference each year from the long term median) over time on the Banjo land system at Larrimah.

What would a drier cycle of the climate mean for your area? Because it’s been wet lately you have probably been able to carry more stock than the long term safe carrying capacity. If you are in the southern VRD you might have been safely carrying closer to 16 AE/km2 on your black soils, the safe level for a 70th percentile year (Table 4). But if the climate switches to a drier period, like 1985 to 1994, suddenly the safe carrying capacity would be more like a 30th percentile year, or 9 AE/km2, almost half what was safe during wetter times.

In the Sturt Plateau the rainfall is higher, so pasture growth varies less year to year (table four) and there’s much less difference between the top 30% and bottom 30% of years in safe stocking rate than for the southern VRD. The central VRD falls somewhere between the other two locations in year to year variability in growth and safe stocking rate.

Because you don’t know when the next failed wet is coming, the best way to manage seasonal risk is to (1) moderately adjust stocking rates seasonally around the long-term safe carrying capacity and (2) don’t exceed safe stocking rates more than one year in three. Degradation events tend to occur when one or more dry years follow a run of good seasons, when stock numbers have increased but are not reduced quickly enough in response to the sudden turnaround in seasons. Unfortunately degradation can happen very quickly, but can take a very long time to reverse, if it can recover at all. Having stocking rates low enough to permit pasture recovery in better seasons is also an important component of keeping your pastures in good condition, so they can make the most of the rain that falls and grow to their potential. Having pre-planned strategies that have inbuilt thresholds and triggers for intervention to quickly respond to changing forage availability will minimise the chance of degradation events.

It may be about to get drier. History repeats through cycles of drier and wetter seasons. We’ve just had two decades of amazing rainfall and growth. What is your contingency plan for when seasons are drier again?

- Do you have spare ungrazed areas?

- Do you have animals built into the system that can be easily offloaded?

- When will you move or sell stock?

- Do you have decision points during the wet season that trigger action?

Is your planned level of development economically sustainable if we now have two decades of drier seasons? Hope for the best but plan for the worst.

Alluvial land type | Grassland Southern VRD | Open woodland Central VRD | Open woodland Larrimah, Sturt Plateau | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Percentile year | 10 | 30 | Median 50 | 70 | 90 | 10 | 30 | Median 50 | 70 | 90 | 10 | 30 | Median 50 | 70 | 90 |

Rainfall (mm) | 309 | 424 | 519 | 617 | 787 | 436 | 588 | 703 | 799 | 942 | 512 | 640 | 763 | 889 | 1147 |

Pasture growth (kg/ha) | 550 | 1290 | 1660 | 2290 | 3430 | 1300 | 1780 | 2310 | 2600 | 2730 | 1940 | 2380 | 2870 | 3440 | 3740 |

Safe stocking rate (AE / km2) | 4 | 9 | 11 | 16 | 23 | 9 | 12 | 16 | 18 | 19 | 13.5 | 16 | 19.5 | 23.5 | 25.5 |

Red soil land type | Short grasses, southern VRD | Perennial grasses on limestone, central VRD | Gravelly red soils at Larrimah, Sturt Plateau | ||||||||||||

Pasture growth (kg/ha) | 390 | 740 | 970 | 1280 | 1910 | 740 | 1030 | 1270 | 1590 | 1960 | 1355 | 1708 | 2030 | 2360 | 2500 |

Safe stocking rate (AE / km2) | 1 | 2.5 | 3.5 | 4.5 | 6.5 | 4 | 5 | 6.5 | 8 | 10 | 7 | 9 | 10.5 | 12 | 13 |

Table 4: Seasonal variation in pasture growth and safe stocking rate for three locations and two land types over the last 126 years in ‘A’ condition.

Give feedback about this page.

Share this page:

URL copied!