Livestock disease investigations

The department provides a free disease investigation service to livestock owners for diagnosis of notifiable emergency, exotic and endemic disease, including zoonotic diseases. Berrimah Veterinary Laboratories provide free diagnostic testing for exclusion of notifiable diseases for all disease investigations, and subsidies are available for producers to contact private veterinarians for significant disease investigations in livestock.

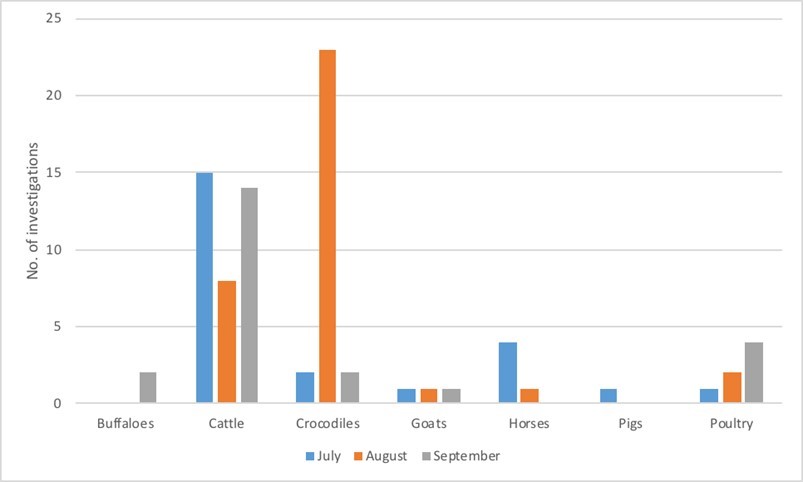

During July to September 2018, 83 livestock disease investigations were conducted to rule out emergency diseases or investigate suspect notifiable diseases across the Northern Territory.

Image above: Livestock disease investigations in the NT, July to September 2018

Tick fever in bulls in a holding yard

A large group of age-cull bulls from multiple properties were being held in a holding yard in the cattle tick-infected zone prior to sale during June and July. Over this period, the manager noticed some bulls had diarrhoea, and seemed tucked up and lethargic before showing an uncoordinated gait and tremors. The manager became concerned when a number of these bulls died, and contacted the government who attended the property the same day to conduct autopsies.

A private and a government veterinarian conducted autopsies on two bulls from two consignments. One bull had died over 12 hours previously. The carcase was severely decomposed making it difficult to interpret cause of death. A full range of samples were collected and submitted to the laboratory as the first case. The autopsy on the second bull a week later showed mild jaundice, port wine-coloured urine and haemorrhages on a number of mucosal surfaces. There were small fragments of ironwood leaves in the rumen content.

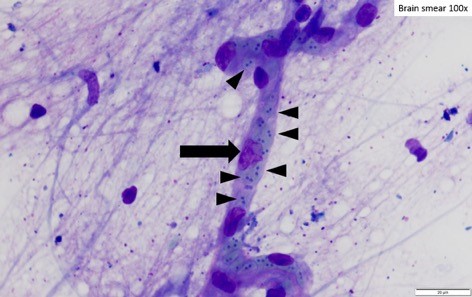

Laboratory testing of the decomposed bull showed no explanation for any of the signs noted. Referral testing was performed on brain and kidney samples and was positive for Babesia bovis (B bovis) and B. bigemina. Tick fever was suspected but could not be confirmed due to the lack of findings given the decomposed state of the carcase. Test results for the second case revealed significant parasitism with B. bovis, confirming a diagnosis ofbabesiosis (Figure 3). Due to the neurological signs seen before death, transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE) was excluded in both bulls.

Babesiosis or ‘tick fever’ is a disease of cattle caused by blood parasites that are transmitted by the cattle tick. On further questioning it became apparent that the bulls affected had originated in a cattle tick-free zone and not been treated for ticks before moving to a holding property, which was in a tick-infested zone. Cattle born and raised in areas where cattle ticks are endemic can develop natural immunity through exposure to ticks infected with tick fever. Cattle raised in areas free from cattle ticks are at risk of tick fever if introduced into areas where ticks are present. The bulls were vaccinated (‘blooded’) as young bulls. Juvenile bull vaccination is no guarantee of life-long protection against the tick fevers. Other classes of cattle did not show any apparent disease which may be due to their genetics or some less apparent factor.

In this case, management advice was given to treat and remove ticks from affected cattle and there were no further losses. The property where the bulls had originated was also given advice to ensure that any at-risk cattle are blooded (vaccinated for tick fever) prior to moving them into the tick zone in the future.

Image above: A blood vessel containing red blood cells and basophilic intra-erythrocytic pear-shaped organisms consistent in size and shape with Babesia bovis. Arrow heads point to blood cells containing organisms.

Give feedback about this page.

Share this page:

URL copied!