Pregnancy toxaemia in cattle

Pregnancy toxaemia (also known as Fatty Liver Disease), occurs when cows in good condition with high nutritional demands of late pregnancy cannot get enough feed to meet their energy requirements which leads to a state of negative energy balance. This is a situation when a cow's energy requirements are greater than her dietary energy supply. Under these conditions, cows respond by using their body fat reserves to provide the required energy. In some cases this causes serious metabolic changes, liver damage and even death.

Pregnancy toxaemia is not commonly seen in rangeland cattle but can occur on occasion, mainly due to high levels of stress during late pregnancy. Pregnancy toxaemia is usually triggered by a sudden reduction in feed availability or quality. For example, changing paddocks, mustering long distances, transporting and yarding may cause stress and a reduced feed intake in heavily pregnant cattle. This in turn triggers an increase in body fat mobilisation to the liver to meet energy demands.

What causes fatty liver disease?

Pregnant cows require large amounts of energy to maintain their growing calf. This energy comes in the form of glucose from two processes:

- Feed is absorbed in the rumen and transported to the liver where glucose is produced.

- Body fat is also broken down and transported to the liver via the bloodstream where the liver converts it to glucose during times of high energy demand such as late pregnancy.

The negative energy balance is created when the amount of glucose produced by the liver to break down the incoming body fat is not enough. This causes the fat to start building up in the liver. The liver then becomes enlarged, pale and fatty. Another disease that often affects cows simultaneously as a result of these metabolic changes occurring is called ketosis. Ketones are a by-product of this fat burning process to access energy. Excessive levels of ketones build up in the brain and tissues and may cause some of the clinical signs often associated with pregnancy toxaemia. These include:

- depression

- inappetance (not eating)

- ataxia (weak in the hind end)

- recumbent (unable to stand)

- increased respiratory rate

- increased aggression, stubbornness or confusion.

Prevention

Pregnancy toxaemia may be prevented by management strategies that maintain a good appetite and supply of adequate feed to meet this demand of energy during the late stages of pregnancy and immediately after calving when milk and energy demands are high. These strategies include:

- minimising stress by avoiding mustering, transport and prolonged yarding of heavily pregnant animals (all of these factors may reduce feed intake and cause an increase in fat mobilisation to the liver). Pregnant cows with a high body condition score seem to be more susceptible to pregnancy toxaemia if they are starved for short periods; for example, if yarded for several hours or transported.

- feeding ample quantities of high-quality forages during the last trimester and post calving to meet energy demands.

It is a major reason for the restrictions in the Land Transport Standards that must be followed:

- SB4.3 Cattle known to be in the last four weeks of pregnancy must only be transported under veterinary advice unless the journey is less than four hours duration.

Diagnosis and treatment

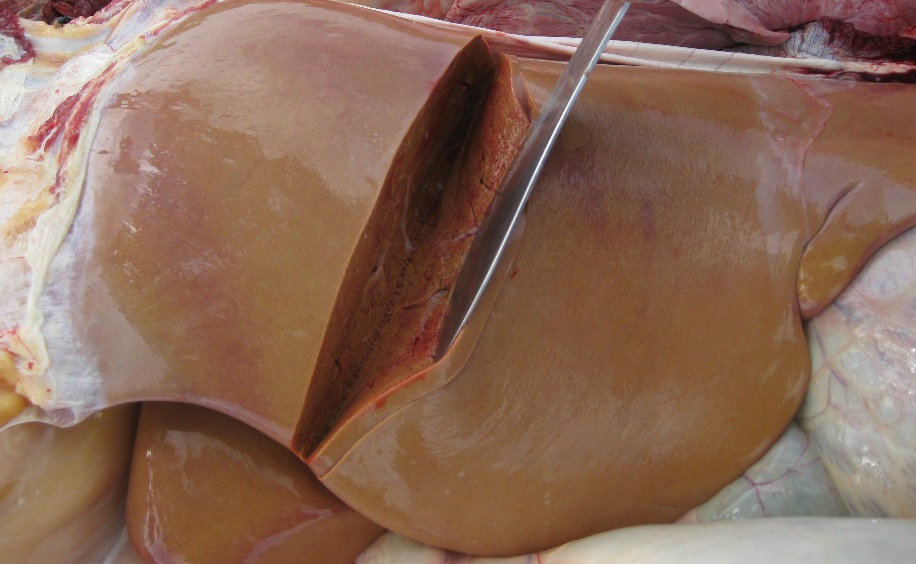

In extensive field conditions diagnosis is normally confirmed by blood tests and/or a post mortem examination of an affected animal. The liver is normally very large, pale and tears easily. Treatment usually comprises intravenous fluids and oral Propylene glycol over an extended period of time. Treatment options are limited in larger cattle station conditions due to the extensive nursing care and time required for the recovery of affected animals (may be weeks).

Figure 3: A fatty liver (left) and a normal liver (right)

Once the metabolic changes of pregnancy toxaemia begin to occur in an animal they are very difficult to reverse. Diagnosis in one or two individual animals may indicate a dietary energy deficiency being experienced by the whole herd or a sudden stressful event. Awareness of this condition, early detection and prevention by providing careful management including; good quality grazing or supplementary feed during the last trimester of pregnancy has proven to be more effective than treatment.

Give feedback about this page.

Share this page:

URL copied!