Zamia poisoning in cattle in the Katherine region

Megan Pickering, Katherine Regional Veterinary Officer

Cycads or zamia palms in Australia, belong to an ancient family of plants which have existed since the Mesozoic era, pre-dating flowers, grasses and trees. They were the cause of the first documented plant poisonings by European explorers: Vlaming (1697), Cook (1770), La Perouse (1788) and Flinders (1801) all mention consumption of zamia palm as the cause of sickness in men, pigs and cattle1.

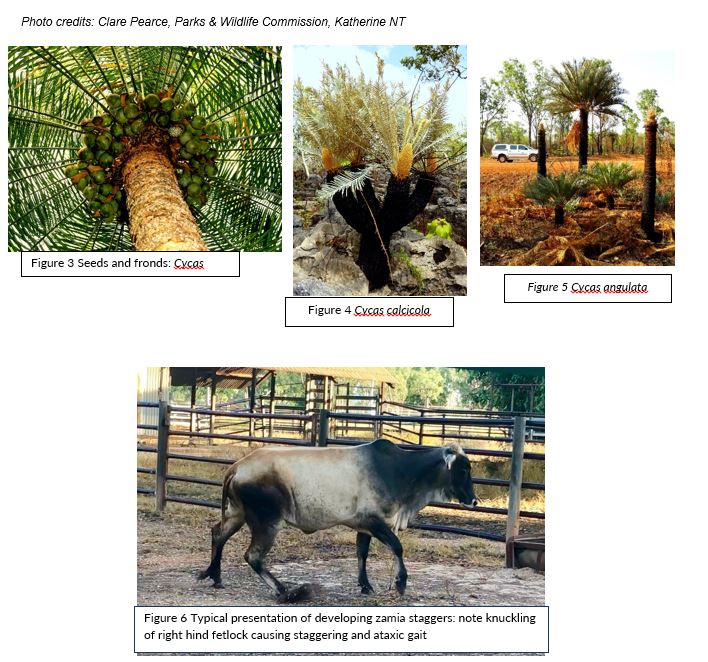

Cycad genera are likely to cause toxicity syndromes in livestock are Cycas, Macrozamia and Bowenia; in the Northern Territory; they are primarily found around the Top End and in coastal areas around the Gulf of Carpentaria. The plants have palm-like leaves arranged in a rosette formation around a single trunk, which in most species remains quite low to the ground, and is therefore easily accessible to grazing livestock (see Figures 3-6). The leaves, seeds and roots contain at least two toxins: an unidentified neurotoxin which causes irreversible damage to the spinal cord in cattle, and cycasin which, when metabolised to formaldehyde and methylazoxymethanol (MAM), is hepatotoxic in herbivores, pigs, dogs and humans2. Early explorers who ate small amounts of cycad nuts suffered from severe vomiting and diarrhoea; modern case reports include accidental poisonings of small children and dogs who have developed fulminant liver necrosis with devastating consequences3.

Livestock may graze cycads when other feed is scarce or if new shoots and leaves are within easy reach; seeds and young fronds appear to be quite palatable, but are most likely to be consumed during very dry conditions or when re-growth appears after a bushfire. In cattle, chronic exposure leads to progressive and irreversible paresis or paralysis, which producers may refer to as ‘wobbles’, zamia staggers or (mistakenly), ‘rickets’4. Ataxia and paralysis result from degeneration of nerves in the mid-cervical and lumbar spinal cord, both of which should be included as sampling sites for histopathologic diagnosis. Laboratory findings include bilateral demyelination and axonal degeneration of the spinal cord. Clinical signs may develop as soon as 14 days after eating the plants, or may be slowly progressive over a number of years, and initially include:

- Goose-stepping gait in the hind limbs

- Knuckling of the hind fetlocks

- Wasting of the hindquarters

Differential diagnoses to consider in cases of chronic bovine neurological disease include:

- Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy

- Rabies

- Tetanus

- Encephalomyelitis

- Sarcostemma poisoning

- Space-occupying lesion of the central nervous system – abscess, cyst, neoplasia

- Lead poisoning

- Botulism

Affected cattle do not improve as the changes to the central nervous system are irreversible. Cattle may die from misadventure (falling into ditches, gullies and watercourses) or may perish when they become too weak to access water. Despite the meat being unaffected, animals exhibiting clinical signs are not suitable for slaughter through abattoirs as they are not fit to load for transport. There have been a number of confirmed cases of zamia poisoning on properties in the Katherine region over recent months; some animals are native-born, while others have been purchased from elsewhere in the NT or from Queensland, with clinical signs developing sometime after purchase. In each case, cattle have presented with progression of signs of knuckling (see image, page 2), falling/staggering and plaiting of the hind limbs, increasing debilitation, weight loss, and inability to rise and eventually, either death or humane destruction has resulted.

Control of cycads may be problematic for livestock producers. Many cycads are protected under conservation laws and cannot be destroyed. One solution if production losses are significant, is to fence off zamia country and limit access to it unless grazing is plentiful and cycads are not in an active growth phase. Diagnosis of zamia staggers is presumptive in the field (based on clinical signs, access to plants and evidence of grazing), but definitive confirmation is made on post-mortem histology in the laboratory. Animals with suspected zamia staggers are suitable for TSE-exclusion testing, which attracts a producer subsidy under the National TSE Freedom Assurance Program. This programs provides evidence to support international market access for the cattle industry.

Common Cycad species of the Northern Territory:

References

- Hall, WTK 1964 – cited in Cycad (zamia) poisoning in Australia Aust Vet Journal Vol.64 No.5 May 1987: 149-151

- Australia’s Poisonous Plants, Fungi and Cyanobacteria – A guide to species of medical and veterinary importance. McKenzie, R. CSIRO Publishing 2012 p.122-138

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1939-1676.2011.00755.x

- Whiting MG.Toxicity of cycads. Economic Botany1963;17:270–302.

Give feedback about this page.

Share this page:

URL copied!